Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology

Short Communication

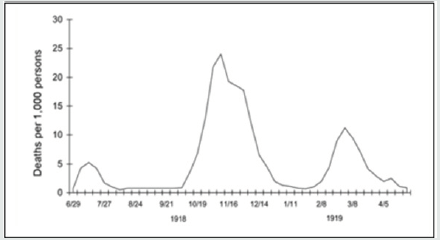

CHistory does not repeat itself. Though every single historical

moment is distinct, parallels can be drawn between different historical

events. Even though history does not teach us what to do, it can inspire

us to act. Revising the 1918 influenza pandemic is an opportunity to

consider the current coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis from a different

perspective. Influenza and coronavirus share basic similarities in the

way they are transmitted via respiratory droplets and contact surfaces.

Descriptions of H1N1 influenza patients in 1918-19 resemble the

respiratory failure of COVID-19 sufferers a century later. Current

discussions about holding back social distancing measures and opening

the country frequently refer to “waves” of disease that characterized

the dramatic mortality of H1N1 influenza in three major peaks in

1918-19. As COVID-19 rates begin to stabilize in some parts of the U.S.,

people today are nervously eyeing the “second wave” of influenza that

came in autumn 1918, that pandemic’s deadliest period.The 1918 influenza

pandemic took place during the First World War with three successive

waves: the first in the spring of 1918, the second – and most lethal,

responsible for 90% of deaths – in the autumn of 1918, and a final one

from the winter of 1918 to the spring of 1919. By the end of it, more

than half of the world’s population had been infected. Estimations on

mortality, showed a broad spectrum ranging from 2.5 to 5% of the world’s

population, which translates to between 50 and 100 million deaths. The

pandemic was, therefore, five to ten times deadlier than the First World

War.

Waves evoke predictability, however, and COVID-19 has been hard to

predict. Despite the lessons drawn from past influenza outbreaks, how

pandemic influenza struck in 1918 is not an exact template for what can

happen with COVID-19 in the upcoming months [1].The 2020 coronavirus and

1918 Spanish influenza pandemics share many similarities, but they also

diverge on some points. Here we empathize some of those points.

According

to Deutsche Bank, a major difference between Spanish flu and COVID-19 is

the age distribution of fatalities. For COVID-19, the elderly has been

hit the worst. For the Spanish flu of 1918, the younger population were

severely affected. The death rate from pneumonia and influenza that year

among the middle-aged population in the United States was more than 50%

higher than that for the older population. Back to COVID-19, the

overall mortality rate measured by weekly new deaths and weekly new

cases is around one-third of the level observed in the second half of

April which shows a decline in the current wave [2].Over 500 million

people, or one-third of the world’s population, became infected with the

1918 Spanish flu. According to the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, approximately 50 million people died worldwide, with about

675,000 deaths occurring in the US. They added that during the pandemic,

mortality was high in three categories of people: younger than 5 years

old, 20-40 years old, and 65 years and older. The high mortality in

healthy people, including those in the 20-40-year age group, was a

unique feature of this pandemic. With no vaccine to protect against it

and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections that can be

associated with it, controlling the disease worldwide were limited to

non-pharmaceutical interventions.COVID-19, the disease caused by the

virus SARS-CoV-2, has already proved extremely infectious. According to

Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering,

it had approximately infected 13.1 million people globally and more than

3.4 million in the U.S. The disease had killed at least 573,664 lives

worldwide and 135,615 in the U.S.As for Symptomatology, for both

COVID-19 and flu, one day or more can pass between a person becoming

infected and when he or she starts to experience illness symptoms.

However, if a person has COVID-19, it usually takes longer to develop

symptoms than if they had flu. For the flu, a person develops symptoms

anywhere from 1 to 4 days after infection but for COVID-19, symptoms can

appear as early as 2 days after infection or as late as 14 days after

infection,

and the time range can vary [3].

Being firstly identified in the Chinese city of Wuhan, some have labeled COVID-19 the ‘Chinese virus’. Stigmatizing a group or a nation for its alleged responsibility in a calamity is not a new trend. Take the misnomer of the ‘Spanish Flu’: unlike most of the countries at war at the time, where censorship was extreme and newspapers were initially not allowed to report on the disease, the Spanish press firstly covered the spread of the virus, creating false assumptions that the epidemic originated in Spain.Many other nicknames were given to the pandemic based on nationality or race, for example: ‘Spanish Lady’, ‘French Flu’, ‘Naples Soldier’, ‘War Plague’, ‘Black Man’s Disease’, ‘German Plague’, or even the ‘Turco-Germanic bacterium criminal enterprise’.War censorship and propaganda also had adverse effects on efforts to mitigate the pandemic. By attempting to censor information on the seriousness of the situation, many belligerent countries most certainly hindered public health efforts to stem the pandemic. Many people did not understand how the flu, an ordinarily mild illness, could cause so many deaths. Some believed their government was lying and trying to hide the return of typhus, cholera, or a so-called ‘pneumonic plague’. In Germany, some people accused the government of using a fake pathogen as a pretext to hide the deaths that were caused by malnutrition and exhaustion according to them.The lives lost during that old pandemic teach us that transparent information is essential at all times(Figure 1). To follow public health measures, the population needs to trust the authorities. In 1918, after four years of conflict and propaganda, that trust was broken. This is even more true in 2020. Mistrust of information from health authorities is still a challenge. Modern means of communication and the digital social networks make it even harder. Undocumented claims, false information, conspiracy theories, and dangerous conclusions can spread as quickly as viruses [4,5].

Figure 1: Three waves of death during the pandemic: weekly combined influenza and pneumonia mortality, United Kingdom, 1918–1919. The waves were broadly the same globally[5].

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Read More Lupine Publishers Otolaryngology

Journal

Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-otolaryngology.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment