Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology

Abstract

Background: Obstructive sleep apnea and hypopnea syndrome (OSA) is defined as a reduction or cessation of the airflow in the human airway. It effects nearly 18 million Americans and weight gain is the main predisposing factor. In this study, we aimed to investigate the effects of apnea and hypopnea individually.

Material and Methods: 83 participants were included in the study and they are divided into two groups as apnea predominant or hypopnea predominant. Pittsburg quality of sleep index (PQSI) and Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) are completed for all subjects and full-night attended polysomnographic evaluations are done.

Results: ANOVA test was used to compare the inter-group variances. Between the two study groups, no statistical significance was reported between the PSQI or ESS scores.

Conclusion: The effects of apnea and hypopnea are similar on sleep quality or day-time sleepiness, however further studies also investigating the duration of the events as well are needed.

Abbreviations: OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea/Hypopnea Syndrome; PSG: Polysomnography; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea and hypopnea syndrome (OSA) is reviewed under the sleep related breathing disorders. The diagnostic criteria must satisfy daytime sleepiness, fatigue or nonrestorative sleep, waking up with breath holding, gasping or choking, witnessed apnea periods and comorbidities such as hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease or type 2 diabetes mellitus may accompany the disease. The full-night polisomnography (PSG) must demonstrate at least five obstructive respiratory events (apnea, hypopnea, respiratory effort related arousals) per hour of sleep (apnea/hypopnea index, AHI), but AHI below 15 needs the abovementioned signs for a complete diagnosis [1]. OSA may be seen in any age group, nevertheless published data from several countries indicate that OSA associated with daytime sleepiness occurs in 3% to 7% of adult men and 2% to 5% of adult women. However, because many individuals with OSA do not endorse daytime sleepiness, the prevalence of the disease is likely much higher [2]. The major predisposing factor for OSA is excess body weight. It has been estimated that nearly 60% of moderate to severe OSA is attributable to obesity. The risk of OSA increases as the degree of additional weight increases, with an extremely high prevalence of OSA in people with morbid obesity [3]. Several factors are implicated in the development of OSA [4].

The main cause addresses the reduction of the expansion forces of the dilator muscles of the upper airways. The capacity of the muscles decreases more during the REM sleep. Additional factors are excessive or elongated tissues of the soft palate, macroglossia, tonsillar hypertrophy, and a redundant pharyngeal mucosa [5]. OSA and comorbidities such as stroke, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases or endocrinologic disorders are well taught in years, however the individual effects of apnea or hypopnea alone are never considered. To best of our knowledge, the published data does not mention which entity alone is more harmful to systemic functions or at least sleep, apnea or hypopnea? The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is an effective instrument used to measure the quality of sleep in the adult. It differentiates “poor” from “good” sleep by measuring seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction over the last month. A global sum of “5” or greater indicates a “poor” sleeper [6]. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a self-administered questionnaire with 8 questions. Respondents are asked to rate, on a 4-point scale, their usual chances of dozing off or falling asleep while engaged in eight different activities. The higher the ESS score, the higher that person’s daytime sleepiness and scores higher than 10 are significant. In this study, we compared apnea versus hypopnea due to the sleep quality and daytime sleepiness individually.

Materials and Methods

Between July 2017 and January 2019, 327 cases complaining of snoring, daytime sleepiness and witnessed sleep apnea periods were referred to full-night polisomnography. 150 cases were diagnosed as OSA were enrolled in the study. After the final assessment, a total number of 83 participants were chosen. The ethical committee approval was taken from Okmeydani Training and Research Hospital (48670771–514.10) and informed consent are taken from all participants.

PSG

3 Channel EEG (F4-M1, C4-M1, O2-M1), 2 channel EOG, chin, right and left tibialis anterior EMG, body position sensor, oro-nasal thermal sensor, nasal pressure sensor, thoracic and abdominal sensors, ECG, pulse-oximetry and synchronous video recordings and breath sound recordings were the parameters recorded through the night. The examination, sleep and wake periods and sleep related disorders were scored according to the criteria of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine [7].

Clinical Examination and Laboratory Tests

All participants underwent a detailed otolaryngologic examination including the fiberoptic naso-pharyngolaryngoscopy. Mueller maneuver was made to detect the pharyngeal collapse, vallecula epiglottica was visualized to assess the bulkiness, Friedmann Tongue Positions and Tonsil Gradings are made to determine the glossopharyngeal patency. Complete blood count and routine biochemical blood tests including the thyroid function tests were studied. PSQI and ESS were completed for each participant.

Study Design

In order to emphasize the individual effects of apnea or hypopnea, each PSG were examined and if apnea was higher than hypopnea by 50% or vice versa, that participant was included in the study. The study group, therefore, was divided into two as apnea predominant (AP) and hypopnea predominant (HP). Comorbid pulmonary or neurologic disorders, sleep disorders other that OSA (Central sleep apnea, Hypersomnolence, Parasomnias, Circadian rhythm disorders, etc.) were excluded. Also, pediatric population were not included in the study.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM SPSS, Turkey). Continuous data was displayed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was a p-value of greater than 0.05. A Shapiro–Wilk test showed the normal distribution of the parameters. ANOVA test was used to compare the normally distributed inter-group comparisons of the descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, and frequency) and the quantitative data.

Results

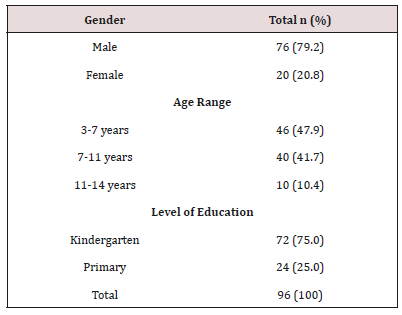

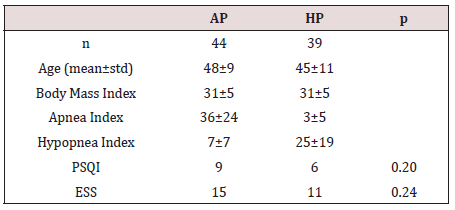

A total number of 83 participants aged between 24–64 years (mean 46±10 years) were studied. 61 were male (73.49%) and 22 were female (26.51%). The inter-group characteristics are shown in Table 1. The PSQI between AP and HP groups were not statistically significant (p=0.205). Similarly, ESS between AP and HP groups were also not statistically significant (p=0.240) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: AP versus HP by means of PSQI and ESS.

Table 1: Subject characteristics and statistical comparisons.

ANOVA test showed no statistical significance among variances.

OSA is defined as the reduction or cessation of airflow for at least ten seconds. The entity is almost every time in association with snoring, and between the snores, airflow may stop completely (apnea) or reduction in the airflow (hypopnea) may happen. If there is a body effort to breathe, the disease is termed obstructive, otherwise it is central. In the presence of a collapsible airway, sleepinduced loss of tonic input to the upper airway dilator muscle motor neurons allows the pharyngeal airway to collapse [8]. The general reaction to this airway obstruction is arousal; sleep then resumes, leading to repeated cycling of sleep, intermittent hypoxia, and arousal throughout the night. Neurocognitive effects of OSA include daytime sleepiness and impaired memory and concentration; cognitive impairment and neural injury may develop in association with sleep apnea [9,10]. Sleep-disordered breathing and OSA are not reported frequently in animals but a natural animal model

Discussion

OSA is defined as the reduction or cessation of airflow for at least ten seconds. The entity is almost every time in association with snoring, and between the snores, airflow may stop completely (apnea) or reduction in the airflow (hypopnea) may happen. If there is a body effort to breathe, the disease is termed obstructive, otherwise it is central. In the presence of a collapsible airway, sleepinduced loss of tonic input to the upper airway dilator muscle motor neurons allows the pharyngeal airway to collapse [8]. The general reaction to this airway obstruction is arousal; sleep then resumes, leading to repeated cycling of sleep, intermittent hypoxia, and arousal throughout the night. Neurocognitive effects of OSA include daytime sleepiness and impaired memory and concentration; cognitive impairment and neural injury may develop in association with sleep apnea [9,10]. Sleep-disordered breathing and OSA are not reported frequently in animals but a natural animal model of OSA is English bulldogs, which have been used to study upper airway anatomy and physiology and the pharmacologic treatment of OSA. English bulldogs have an enlarged soft palate and narrow oropharynx and display many of the clinical features of OSA, including snoring, sleep-disordered breathing, oxyhemoglobin desaturation during sleep, frequent arousal from sleep, and hypersomnolence with shortened sleep latencies [11]. OSA in English bulldogs is not related to obesity, as it often is in humans. OSA has been modeled in a variety of species by using surgical tracheostomy and subsequent intermittent occlusion of the endotracheal tube [12]. Schoorlemmer et al. [13] produced obstructive apnea in conscious rats by using an inflatable balloon implanted in the trachea and apneic episodes of as long as 16 s in duration could be created during sleep. However, animal models of intermittent hypoxemia have several drawbacks. In many cases, the models mimic severe human OSA and may be less applicable to most clinical OSA. In addition, animals exposed to intermittent hypoxemia develop hypocapnia, whereas human OSA is characterized by hypercapnia. Furthermore, human OSA typically is associated with obesity, which is not always considered in animal studies. In addition, OSA causes sleep fragmentation, which may have independent effects on metabolism. Thus, exposure of animals to intermittent hypoxemia produces repeated arousals and changes in sleep architecture that are comparable to those in clinical OSA, yet the effects may not be persistent, limiting their use for studying long-term metabolic consequences of OSA [14].

Animal models are troublesome to study the long-term effects of sleep fragmentation. The sleep quality is a bio-psycho-social parameter that may never be evaluated in animal models; for example, as we refer to excessive daytime sleepiness, the subject is asked whether the sleepiness occurs in the passive state such as resting periods or during the active periods such as work-time or social interactions. Moreover, the sleep architecture, ultradian rhythm or sleep quality may not be assessed in animal models. In our study, the effects of apnea or hypopnea on sleep quality or daytime sleepiness did not differ. This might have several reasons; first of all, all PSG were done elsewhere, our otolaryngology clinic is not capable to perform full-night attended PSG. This situation has some major drawbacks; it is impossible to mark each breath disorders epoch by epoch on the screen of the test computer, but we rather have a brief report of the night. This makes it impossible to calculate the duration of the respiratory events. Therefore, we only could compare the nature of the events by their scores or numbers (Table 1). Secondly, there are some other factors that may interfere with the sleep architecture such as drops in the oxygen levels; not every subject has the same decreasement in their oxyhemoglobine when they have the same level and duration of airway collapse. Thirdly, limb movements also disrupt the sleep quality and impede normal daytime cognitive functions. Finally, arousals are another issue to study; if OSA is recently developed in the subject, the peripheric chemoreceptors detecting the airflow cessation are more sensitive and arousal happens imminently, if the disease is longer the receptors may become insensitive that happens in sleep continuity despite the airflow cessation. Nonetheless, to best of our knowledge, there is no other study that tried to investigate the effects of apnea of hypopnea individually on sleep quality or daytime sleepiness.

Conclusion

The effects of apnea and hypopnea are similar on sleep quality or daytime sleepiness, however further studies also investigating the duration of the events as well are needed.

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website: h

https://lupinepublishersgroup.com/

For more Journal of Otolaryngology-ENT Research articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/otolaryngology-journal/

https://lupinepublishersgroup.com/

For more Journal of Otolaryngology-ENT Research articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/otolaryngology-journal/

To Know More About Open Access Publishers Please Click on Lupine Publishers