Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology

Abstract

The Objective of this article is to Review current literature about performing a turbinectomy associated with Rhinoseptoplasty. Three clinical trials with level one of evidence about the issue have been published recently. All of them selected patients with nasal obstruction who were submitted to Rhinoseptoplasty. The NOSE scale to measure quality of life in these patients was used. Other tools of objective measurement as Acoustic rhinometry and rhinomanometry or subjective scales, Snot-20 WHOQOl and ROE were also explored. Each study used a different technique for turbinate reduction. All of the three found the same results discussed below. To review the scientific evidences of these articles can bring new outlook about this controversial topic.

Abbreviations: QOL: Quality of Life; NOSE: Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation; ROE: Rhinoplasty Outcome Evaluation

Mini- Review

Rhinoplasty is often performed to restore nasal function and

form. The development or maintenance of nasal obstruction after

rhinoplasty is a complication that negatively affects quality of

life (QOL), and priority should be given to prevention strategies

[1]. However, the available surgical techniques to prevent this

obstruction have been empirically developed and are often

used based on the surgeon’s preference rather than on objective

criteria. Currently, strategies like spreaders grafts, support grafts,

reconstruction or repositioning cartilages and even a good

septoplasty are used to enlarge the nasal valve [2-6]. Another

technique widely used is the Reduction of the inferior turbinate

[3,7-9]. Otherwise, an established technique to reduce turbinate

with hypertrophy is still debatable [10-13]. Reviews pointed

that research in this field appears to be driven by technological

advancement rather than by establishment of patientsʹ benefit.

Partly, because of the lack of properly conducted randomized

controlled trial with long term results. Some articles even question

the efficacy of this procedure in cases of nasal obstruction explained

for other reasons rather than turbinate hypertrophy isolated [14].

A Recent clinical trial reveal that the association of turbinectomy

with septoplasty, though widespread, does not improve the nasal

obstruction clinical outcomes and can add risks to patients [15].

Therewithal an objective standardized tool that links anatomy

measures with clinical results is not available yet [16]. To address

this issue, Stewart et al. have developed and validated the Nasal

Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale, a disease specific

QOL instrument designed to determine the presence of nasal

obstruction [17]. Since then, several studies have compared

preoperative versus postoperative NOSE scores to assess QOL

associated with nasal obstruction. A recent survey by the American

Society of Plastic Surgeons shows that 90% of surgeons address

the inferior turbinate in at least a portion of their cases, with 8%

routinely reducing the turbinate in all cases. However, 10% of the

respondents in this survey did not address the inferior turbinate

in any of their cases [18]. Such variability in addressing this

potential cause of/risk factor for nasal obstruction deserves closer

attention. Guyuron [19] has pointed out that the position of the

inferior turbinates contributes to airway narrowing after nasal

bone osteotomy. On account of that, surgical treatment of inferior

turbinates seems to be a good option to avoid postoperative nasal

obstruction, which would be great because of the accessibility,

simple technique and relative low risks. Unfortunately, all three

latest trials could not prove any improvement in QOL when the

turbinate reduction is associated even by using different techniques.

Furthermore, to access the turbinate does not seem to improve the

rates of nasal obstruction and satisfaction with respiratory scales

outcomes [20-22].

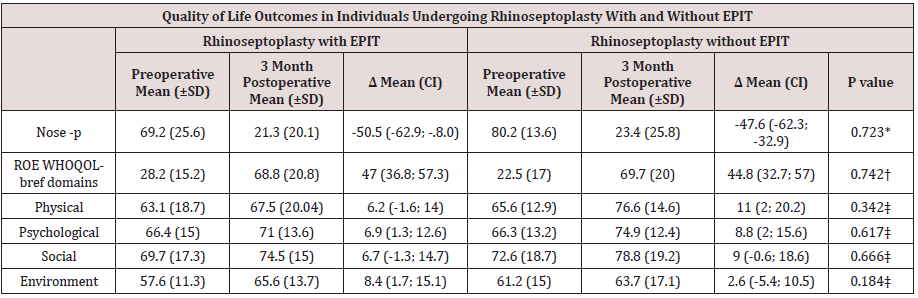

In 2013, Lavinsky-Wolff et al. [20] compared QOL in patients

undergoing primary Rhinoseptoplasty, with or without turbinate

reduction by submucosal electrocautery. There was no difference

between subjects submitted or not to inferior turbinate reduction

in NOSE score (-75% vs. -73%; P = 0.893); all WHOQOL-bref score

domains (P > 0.05), NO-VAS (-88% vs. -81%; P = 0.89) and acoustic

rhinometry recordings (P > 0.05). Besides the literature does

not show difference between the techniques, this study receives

some critique about the conservative reduction by submucosal

electrocautery chosen. In order to answer this question de Moura

et al. [21], in 2017, randomized other 50 patients undergoing

primary Rhinoseptoplasty associated with inferior turbinate

reduction through endoscopic partial inferior turbinectomy (EPIT)

reduction or not. There was no difference between the groups

in absolute score changes for NOSE (-50.5 vs. -47.6; P = 0.723),

Rhinoplasty Outcome Evaluation (ROE) (47 vs. 44.8; P=0.742),

and all (WHOQOL-bref) score domains (P >0.05) (Table 1). There

were no differences between the groups regarding presence

of the complications. Surgical duration was higher in the EPIT

group (212 minutes ±7.8 vs. 159.1±5.6; P > 0.001). Both articles

do not present any improvement at short-term outcomes (three

months). Nevertheless, a long-term result was needed to reinforce

these findings. Wherefore this year Sommer et al. [22] published

a clinical Trial with nine months follow up. They randomized

patients to perform anterior turbinoplasty or not during septo- or

Rhinoseptoplasty.

Table 1: Source de Moura et al. [21].

Dependent variable Δ scores = (postoperative score-preoperative score)

*P Value: ANCOVA of Δ adjusted for baseline NOSE -p value, nasal itching, rhinorrhea and use of spreader graft.

†P Value: ANCOVA of Δ adjusted for baseline ROE score, nasal itching, rhinorrhea and use of spreader graft.

*P Value: ANCOVA of Δ adjusted for baseline WHOQOL -bref score, nasal itching, rhinorrhea and use of spreader graft.

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; CI: Confidence Interval; EPIT: Endoscopic Partial Inferior Turbinectomy; NOSE-p: Nasal

Obstruction Symptom Evaluation Portuguese; ROE: Rhinoplasty Outcome Evaluation; SD: Standard Deviation; WHOQOL-bref:

World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale

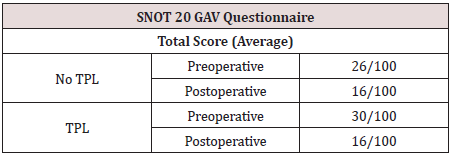

The results enhanced previous trials. Patient satisfaction after functional septo- and septorhinoplasty is high and does not seem to be affected by turbinate surgery. There was no statistically significant difference in the postoperative results regarding objective rhinological measurements with or without turbinoplasty (Table 2). They concluded that extensive resections of the turbinates can have a negative impact on nasal physiology, so the indication for turbinoplasty must be carefully considered. Considering these results, clearly has no reason to proceed a turbinate reduction, at least as routine, to patients submitted at rhinoplasty. As medical science is not so hard, presumably some phenotypes of noses probably could benefit of it. Although these patients are not identified, at least it can be justifying by other reasons, this turbinate access should be avoided. This finding changes the focus of discussion to which method should be used to reduce the turbinate to there are another surgical strategy that could be used to improve our functional results and which technique is it. Be like these finds fortify positively the discussion about structured Rhinoplasty and the importance of the reconstruction and reinforce of the nasal valve.

Conclusion

The indications for the reduction of the turbinate were well established in context of a turbinate inferior hypertrophy [23,24]. The studies have not shown, until now, a superior technique for the inferior reduction. Although techniques which preserve mucosa and have partial resection instead of total resection are indicated [10-12]. Trends in Rhinoplasty research do not show relevant benefits at patients’ quality of life outcomes associated with nasal obstruction when Rhinoplasty is performed combined with reduction turbinate. More clinical trial must be develop comparing other methods of enlargement and preservation of nasal valve and objective measurement instruments need to be developed to clarify these findings [25] (Table 3).

Table 3: Pre-and Postoperative values of the SNOT 20 GAV questionnaire within the groups (TPL vs. No TPL).

Read More Lupine Publishers Otolaryngology

Journal

Articles:

https://lupine-publishers-otolaryngology.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment