Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology

Opinion

Opinion: This editorial is based on my personal professional experiences of some four decades work in health and business applications of statistics. I am fully aware that these experiences cannot be interpreted as a random sample and there is no warranty of any kind for the absence of possible biases. You might well be familiar with the US-FDA view that there is no unbiased data in the scientific universe available. Historically, the use of statistics in medicine is a well-documented fact since about two centuries. My personal experiences cover the transition period from electronic desktop calculators with paper and pencil, to the omnipresence of cheap computing power and sophisticated statistical software of today. I remember my early professional study design activities as a statistician as heavily impacted by cost considerations: Human work time was and still is quite expensive. During the last period of about some two decades I got the strong impression that the medical profession, especially those doctors who are working scientifically – showed a quite strong trend to higher statistical understanding and knowledge as compared to my early working times. This positive trend is highly appreciated by me and I see it as an enormous economic advantage that computers took over the tedious workload of numbers crunching nowadays. There is a negative trend involved over the last two decades as well: I observed a growing trend of numbers of “so called” statisticians who actually are experts in using available statistical software packages only but have little or no statistical expertise. I see a professional statistician as a human who understands the primary objective of the study’s objective and to assess the medical question under consideration and to decide the statistical model selection for the very question based on the scope of the scientific question and all of the constraints and limitations in practice. I know that this is an “ideal world” assumption and we all are but humans with our limitations. My experience that it pays to strive for perfection is illustrated by some examples which I consider to be potentially useful and beneficial for your work as doctor:

Project Planning Phase

a) Overall considerations of project management and quality control, legal requirements.

b) Definition of research question(s).

c) Definition of data selection criteria, sampling variables and observation time(s) schedule.

d) Aspects of data collection and documentation, ongoing project quality controls.

e) Feasibility considerations of various project designs.

f) Administrative aspects: financials, selection of partners, estimation of required realization times.

g) Statistical methods for data analysis, feasibility of pilot- (sub)-projects.

h) Final definition of data selection criteria.

i) Aspects of results publication.

j) Aspects of possibly necessary actions in case of emergencies.

Project Realization Phase

a) Ongoing control of “plan vs actual” progress.

b) Ongoing communication between all project partners.

c) Maintenance of open minds for early signs of project’s critical developments.

d) Ongoing monitoring for possible emergency actions.

e) The KISS principle: Keep everything as simple and stupid as possible.

I’d like to recommend using the items in the above project management as guidance for your project but under no condition as a comprehensive cookbook! As ENT scientist you should permanently remember that you are doing research in humans and not in bolts and nuts!

How you could easily detect the difference between a

“user of statistical software” or a “real” statistician

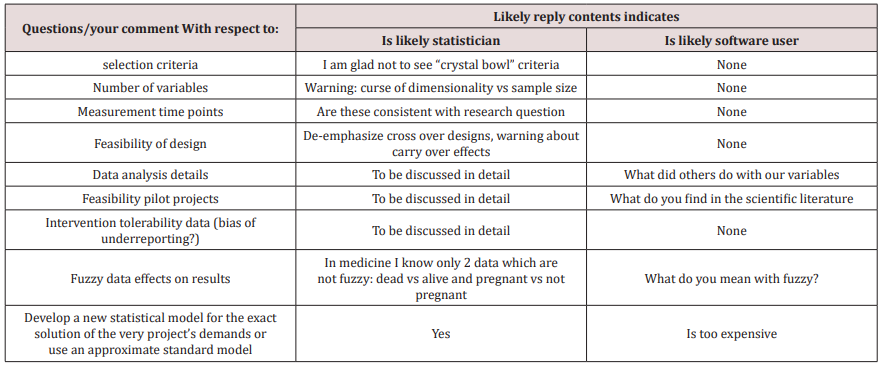

The next table provides you with selected questions/topics to distinguish between professional statistician and software user (Table 1). For more Lupine Publishers Pinterest Click on Below link

https://www.pinterest.com/lupineonlinegroup/

No comments:

Post a Comment